Law enforcement has been universally recognized as a stressful profession. Police officers often observe, deal with, or become involved in extremely difficult situations and experiences on a daily basis. These events are inherent to the law enforcement profession and accumulate over time, often producing a cumulative stress that is immeasurable. Men and women who choose law enforcement as a profession are told to prepare to deal with the cumulative stress of the job. There is however another form of stress that many officers will face but are unprepared to deal with. This stress is more immediate and intense and is often the result of a singular traumatic event. These traumatic events are often referred to as critical incidents.

Sgt. Chris Moad https://www.cji.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/chrismoad.pdf

International Critical Incident Stress Foundation, Inc. (ICISF) – Handout Resources including Traumatic Critical Incident Stress Info Sheet for Spouses/Families/Significant Others and Critical Incident Stress Information Sheets

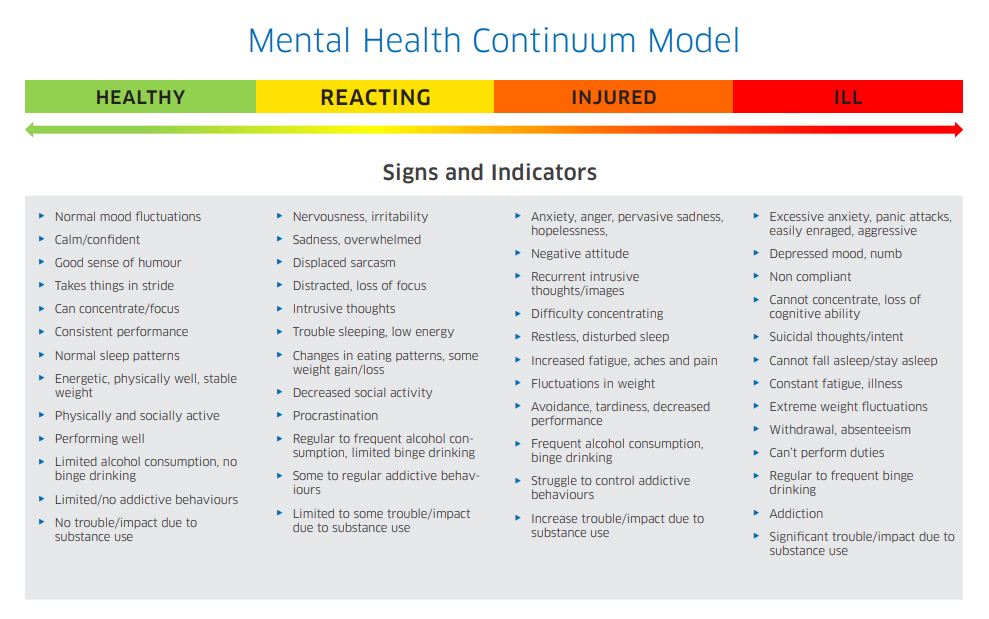

R2MR Scale – Mental Health Continuum Model – The Mental Health Continuum Model reconceptualises how one thinks and talks about mental health, categorizing signs and indicators of good to poor mental health under a four-colour continuum: green (healthy), yellow (reacting), orange (injured and red (ill).

Experiencing a Traumatic Event: Recovery and Coping Strategies by Homewood Health

Stress Management Strategies for Cops – by Dr. Phil Ritchie

The emotional and physical demands involved in serving and protecting can strain even the most resilient person and police officers (like healthcare professionals),are typically more comfortable looking after everyone else’s needs rather than their own. However, if you don’t take care of yourself, you won’t be able to care for anyone else.

To help manage stress:

Focus on what you were/are able to do -control what you can control. It’s normal to feel guilty sometimes; but understand that no one is a “perfect” cop. Believe that you are doing the best you can and making the best decisions you can at any given time.

Set realistic goals. Break large tasks into smaller steps that you can do one at a time. Prioritize, make lists and establish a daily routine. Begin to say no to requests that are not essential and otherwise would be a drain on your limited resources (including time and energy).

Get connected. Isolation can be toxic and can lead to worries about not having the “right stuff” as well as stigmatize any reactions you are having. Talking with supportive peers (often these are the best debriefings) can provide validation and encouragement, as well as problem-solving strategies for difficult situations.

Seek social support. Make an effort to stay well-connected (though perhaps in a socially distanced manner) with family and friends who can offer nonjudgmental emotional support. Set aside time each week for connecting, even if it’s just a walk with a friend. You’re under no obligation to share details of your work, but telling those closest to you “don’t worry” is about as effective as telling a spouse to “calm down” –both typically are the surest fastest way to achieve just the opposite result (don’t try this at home…).

Accept help. If someone asks “how can I help?” be prepared with a list and let the helper choose what they would like to do. Don’t believe that you don’t deserve the support of peers, loved ones, and if necessary, mental health professionals.

Practice good sleep hygiene. Cops, like other shift workers, have issues with sleeping that can have an impact on physical and emotional wellbeing. Good sleep hygiene ensures you are not making sleep worse than it otherwise would be. Avoiding excessive caffeine (if you count your coffee by the pot, it’s likely too much). Napping when you’re not adjusting to shifts can sometimes mess us up. Hours of screen time just before bed are also unhelpful.

Practice Mindfulness. Mindfulness is an evidence-based approach to managing your stress that has also been demonstrated to improve physical wellbeing. Mindfulness Coach is a free app from the Veteran’s Administration in the U.S.

Set personal health goals. For example, set goals to establish a good sleep routine, find time to be physically active on most days of the week, eat a healthy diet and drink plenty of water.

See your physician. Don’t neglect your own physical wellbeing, including recommended vaccinations and screenings. Make sure to tell your doctor that you’re a first responder. And don’t hesitate to mention any concerns or symptoms you have.

Stick with routine. Routine gives us a sense of predictability when our world feels most unpredictable. Routine also fills up time when it’s hard to make even basic decisions about what we should be doing. Keeping busy also means we’re not leaving our minds unoccupied, a void we would otherwise likely fill with traumatic or ruminative thoughts.

Exercise. Exercise can burn off some of the stress and anxiety that often follows a critical incident (check in with your family doctor if this is a significant departure from your usual practice). Non-gory movies, music, and games (board games rather than technology-based) can also provide a healthy escape from the stress.

What went right. In discussing or reflecting upon what’s happened, remember to pay attention to what went right, what was well done, and what was helpful rather than focusing only on the awful part. And don’t be too judgmental when engaging in the inevitable hindsight. You a professional engaged in keeping our society safe, in spite of their being a greater likelihood you’ll be condemned rather than thanked for your efforts.

Schedule self-care/self-compassion. In the course of our professional, and sometimes home responsibilities, we are often more comfortable putting the needs of everyone else ahead of our own. But like the oxygen mask on an airplane, sometimes we need to look after ourselves before taking care of others. Schedule a massage, yoga class, mindfulness practice (a favourite app that’s free is Insight Timer), phone call to a friend or dinner with a loved one as part of your self-care, and then incorporate these events into your regular routine. Incorporate self-care into your routine and not just after a difficult or critical incident.

Give it time. While sadness, anger, resentment and other feelings can linger, most reactions do improve after a little while –in other words, even without intervention by a mental health professional, most people recover. If you that these reactions interfere with your ability to get on with life, then perhaps take time to check in with a friend or a mental health professional.

Phil Ritchie, Psychologist